Art Island 2022

Art Island 2022

Art Island 2022

With Michael Kirkham and Type 42 (Anonymous)

Forteiland IJmuiden

From 3 – 5 March 2022

Openingstijden:

– Donderdag: 16.00 – 22.00

– Vrijdag: 11.00 – 22.00

– Zaterdag: 11.00 – 18.00

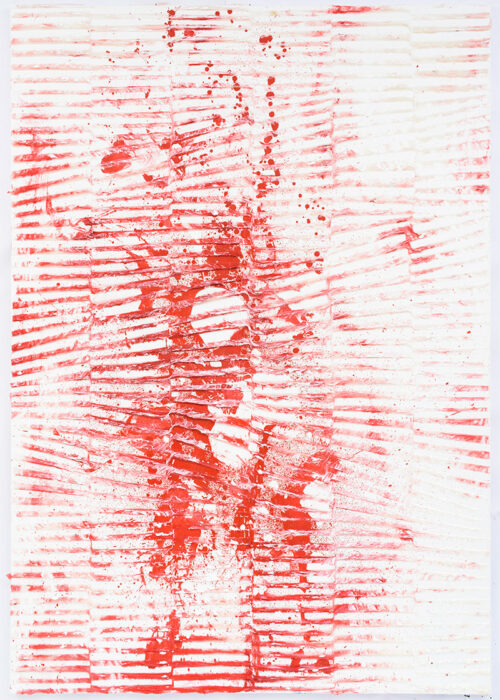

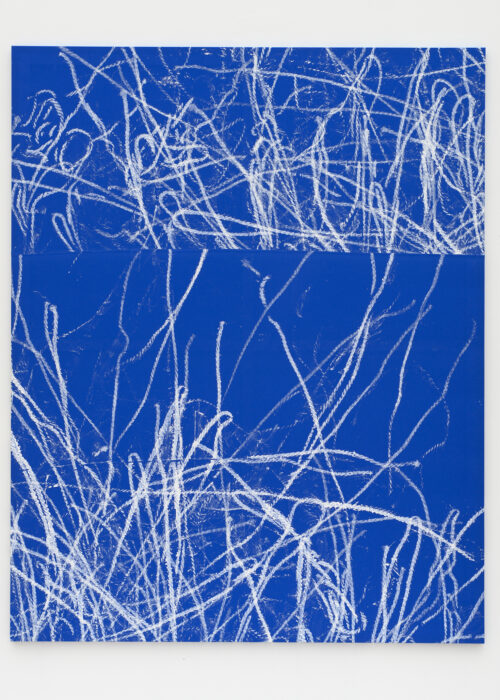

Michael Kirkham

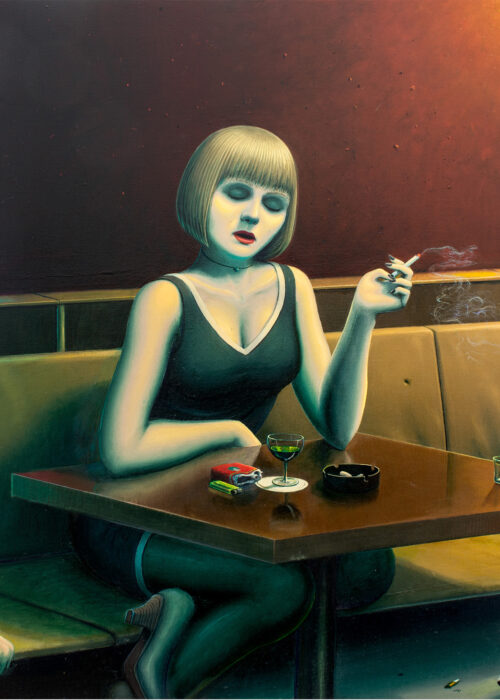

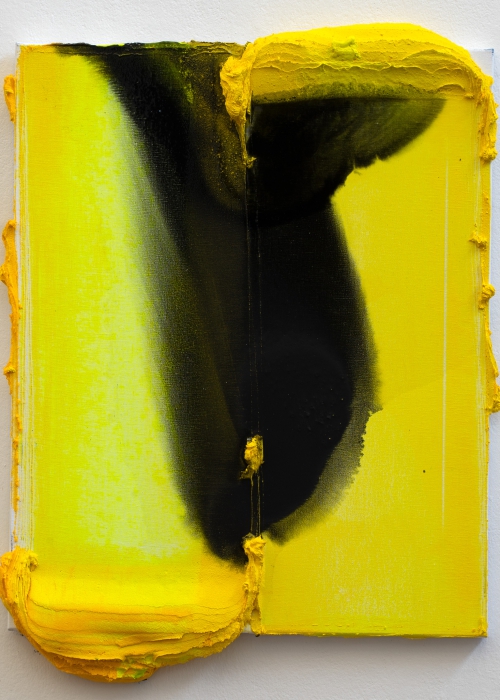

An important aspect of Kirkham’s work is the use of light, yet the source of it differs in every work. Light is also visible in the negative paintings; where we expect shadow, we are greeted with light and where we expect light, a shadow appears. The source appears to come from inside the painting and for that reason the light seems to have a more powerful and stronger impact than a source from outside the painting would have. The playfulness in which Kirkham uses that to highlight the intimate areas of the body and hides the otherwise obvious areas, makes the negatives really intriguing.

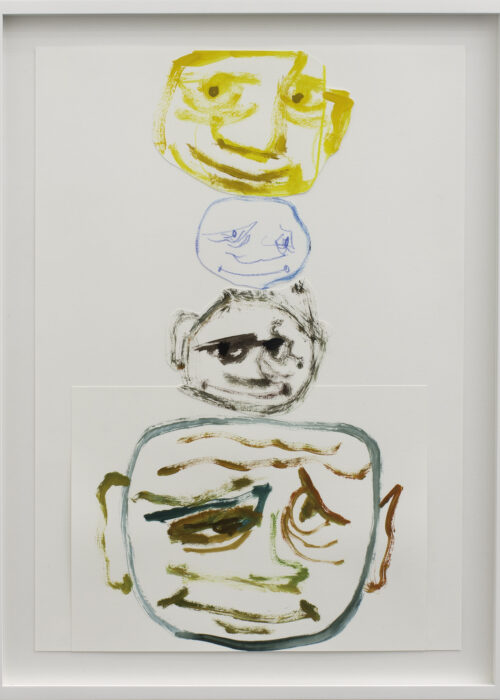

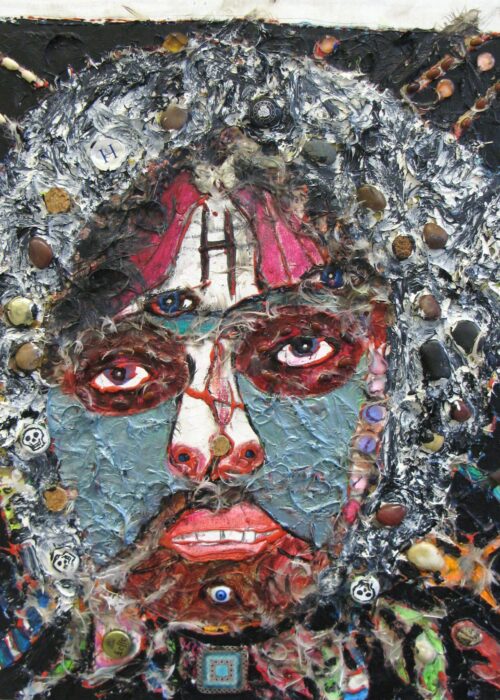

Often highly regarded for their uncompromising nature, Michael Kirkham’s paintings give a delicate insight into the dark corners of human existence. Painted mostly from the mind, mixing fantasy and reality, Kirkham depicts his subjects in uncomfortable or awkward positions, (half) undressed, engaging in acts of sexual nature, being in love, daydreaming, or showing their genitals. While doing so, the characters in Kirkham’s paintings often appear distant, as if disconnected or sunken into the emptiness of their subconsciousness. In addition to the apathetic character of his subjects, most of Kirkham’s paintings appear covered in an apt layer of misery and ambiguity.

As much as these scenes of the despicable bring about a sense of discomfort or voyeurism to the spectator, they are equally intriguing and touching as they display a deep sense of empathy for all aspects of the human condition. This is Kirkham’s power: rather than depicting scenes that exist only in Kirkham’s own artistic universe, his works show those parts of life that, no matter our attempts to disregard or overlook them, are a core part of contemporary life. They show us the alienated or estranged individuals who are no match for the complexities of the world they themselves have helped to build.

It is in this commentary on the contemporary that any sense of melancholy, irony, or even voyeurism so often related to the Kirkham’s paintings disappears. The power and beauty of his work is inseparable from the discomfort it brings about when it confronts the viewer with the bleakness of humanity. Therefore, any form of sadness, irony, voyeurism, or discomfort felt in Kirkham’s paintings can only be a sign of confrontation, recognition or even emotion of the spectator, pointing out to us what essentially makes us human throughout the complexities of today.

The work Man of Sorrows is inspired by the iconic images from the Renaissance of a suffering Christ. A naked and wounded Christ, usually depicted on his knees or from his torso onwards, despised and rejected by man. Man of Sorrows by Michael Kirkham shows the human and contemporary version of this medieval image.

Michael Kirkham (Blackpool, UK, 1971) lives and works in Berlin, Germany. He completed his education at the Glasgow School of Art and De Ateliers, Amsterdam. His work has been exhibited, among many other locations, at Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (NL), Centraal Museum, Utrecht (NL), and Kunstpalast, Düsseldorf (DE), and is part of collections such as the Gemeentemuseum, The Hague (NL), Museum Boijmans van Beuningen, Rotterdam (NL), Centraal Museum, Utrecht (NL), Sammlung Ritter Sport, Stuttgart (DE), Collection Olbricht (DE), Collection SØR Rusche, De Nederlandsche Bank, Amsterdam (NL), and of private collections in The Netherlands, Germany and the United States, among others.

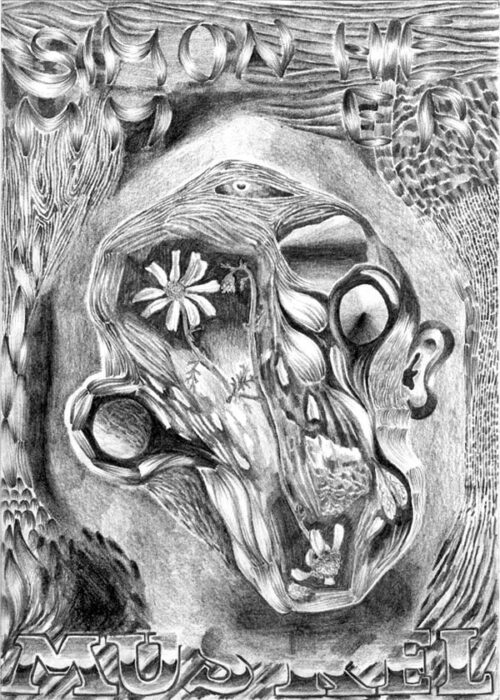

Type 42 (Anonymous)

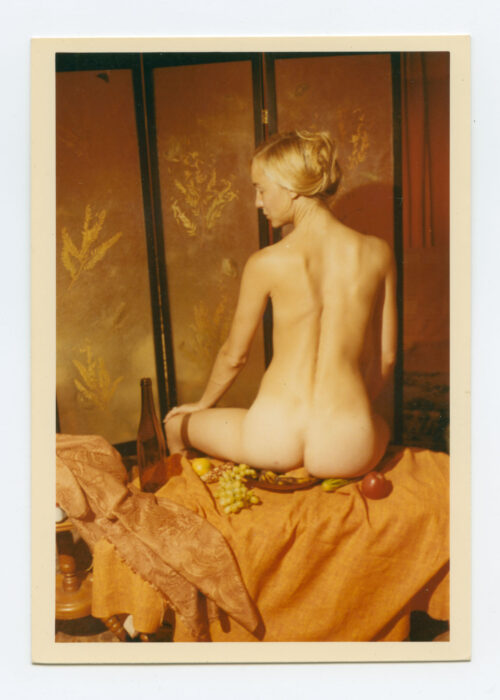

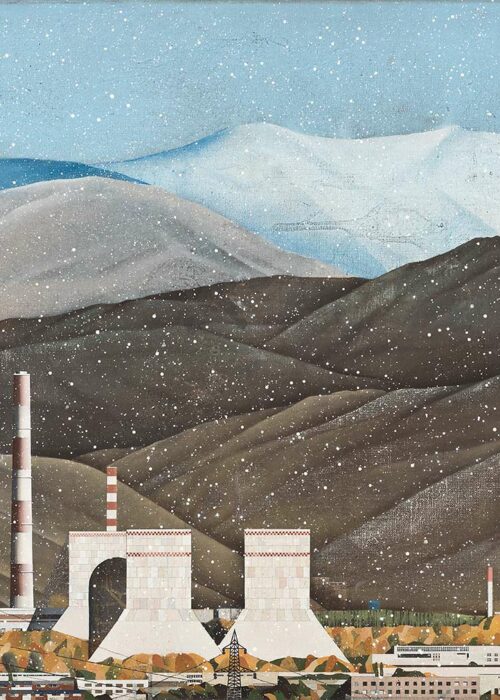

‘Type 42’ is the name of a black-and-white film stock made by Polaroid between 1955 and 1992. In 2012 the artist Jason Brinkerhoff discovered a cache of around 950 images taken on Type 42 film by an unknown photographer, which led to the presentation of the archive at Delmes & Zander Gallery, Berlin, in 2014 and publication of a selection of the photographs in an edition introduced by artist Cindy Sherman. The original photographer is still unidentified, and his or her intentions remain equally obscure.

The photographs feature actresses (and one actor) as they appeared on television and in movies that aired between about 1969 and 1972. They consist mostly of tightly cropped headshots against dark or shadowy backgrounds. The peculiar, emotionally heightened atmosphere of the pictures is often bolstered by distortions introduced by the curvature of the television screen as well as the oblique angle of the shot. Occasionally the frame of the television set is itself visible. Each image has a narrow border of photographic paper, cut with scalloped edges. The visages of the women, sometimes out of focus or overexposed, slide across the surface of the film, anchored by the simple handwritten inscriptions that classify them by name, program, or, in some cases, bodily measurements.

The sweeping inventory of female roles chronicled by the archive offers a panoramic take on the period’s repertoire of popular culture. Spanning age, race, and genre, the subjects include well-known actresses, such as Kim Basinger, Dionne Warwick, Ava Gardner, and Mia Farrow, alongside forgotten and cult figures. Science fiction and low-budget movies appear frequently, attesting to the particular tastes of the photographer. The photographer’s objective can only be surmised based on the desires that seem to drive his or her gaze. The sheer extent of the archive suggests a form of obsession, as does the fact that the photographs were likely taken without the aid of a pause or rewind button, since video recording equipment did not become widely available to the general public until 1971.

Artists

Artists

Type 42 (Anonymous)